| Nocturn to Rosario

Well, then, I am compelled

to say that I adore thee;

to tell thee that I love thee

with all my heart;

that there is much I suffer,

and that much I weep;

that more I can not bear,

and at the cry in which I implore

I entreat thee and speak in the name

of my lost illusions.

At night, when I rest

my temples on my pillow,

and towards another world

I wish to turn my mind,

I walk on, and on,

and at my journey’s end

the forms of my parents

are lost in vacancy,

and thou again returnest

to appear in my heart.

I understand thy kisses

are never to be mine;

I understand that in thine eyes

I ne’er shall see myself;

and I love thee, and in my mad

and ardent deliriums

I bless thy frowns;

I admire thy indifference.

And instead of loving thee less

I worship thee much more.

At times I think of giving thee

my eternal farewell;

to blot thee from my memory

and drown thee in my passion;

but if all be in vain,

and my soul forget thee not,

what wilt thou that I do,

part of my life,

what wilt thou that I do

with this—my heart?

And then, when thy sanctuary

was completed,

thy lamp was burning,

thy veil on the altar.

The sun of the morning

behind the belfry,

the torches emitting sparks,

the incensory smoking,

and there, open in the distance,

the door of my home.

I want you to know

that already many days

have I been ill and pallid

from so much lost sleep;

that all my hopes

have already died;

that my nights are dark—

so black and gloomy

that I know not even where

the future is fled.

How beautiful it would have been

to live beneath that roof,

we two united always,

and always loving each other;

thou always enamored;

I always contented;

we two a soul in one;

we two a single heart;

and between thee and me,

my mother like a god.

Imagine thou how beautiful

the hours of such a life!

How sweet and beautiful the journey

through such a land!

And I dreamed of that,

my holy betrothed,

and when upon it delirating

with my trembling heart,

I thought to be good

for thee, and for thee only.

Well knows God that this was

my most beautiful dream;

my anxiety and my hope;

my happiness and my joy.

Well knows God that in nothing

did I abridge my diligence,

but to love thee much

within the smiling home

that wrapped me in its kisses

when it saw my birth.

Such was my hope—

but now, against its brightness,

is opposed the deep abyss

that exists between the two.

Farewell for the last time,

love of my affections;

the light of my darkness,

the essence of my flowers

my poet’s lyre,

my youth, farewell!

|

Nocturno a Rosario

Pues bien, yo necesito

decirte que te adoro,

decirte que te quiero

con todo el corazón;

que es mucho lo que sufro,

que es mucho lo que lloro,

que ya no puedo tanto,

y al grito que te imploro

te imploro y te hablo en nombre

de mi última ilusión.

De noche cuando pongo

mis sienes en la almohada,

y hacia otro mundo quiero

mi espÃritu volver,

camino mucho, mucho

y al fin de la jornada

las formas de mi madre

se pierden en la nada,

y tú de nuevo vuelves

en mi alma a aparecer.

Comprendo que tus besos

jamás han de ser mÃos;

comprendo que en tus ojos

no me he de ver jamás;

y te amo, y en mis locos

y ardientes desvarÃos

bendigo tus desdenes,

adoro tus desvÃos,

y en vez de amarte menos

te quiero mucho más.

A veces pienso en darte

mi eterna despedida,

borrarte en mis recuerdos

y huir de esta pasión;

mas si es en vano todo

y mi alma no te olvida,

¡qué quieres tú que yo haga

pedazo de mi vida;

qué quieres tú que yo haga

con este corazón!

Y luego que ya estaba?

concluido el santuario,

la lámpara encendida

tu velo en el altar,

el sol de la mañana

detrás del campanario,

chispeando las antorchas,

humeando el incensario,

y abierta allá a lo lejos

la puerta del hogar…

Yo quiero que tú sepas

que ya hace muchos dÃas

estoy enfermo y pálido

de tanto no dormir;

que ya se han muerto todas

las esperanzas mÃas;

que están mis noches negras,

tan negras y sombrÃas

que ya no sé ni dónde

se alzaba el porvenir.

¡Que hermoso hubiera sido

vivir bajo aquel techo.

los dos unidos siempre

y amándonos los dos;

tú siempre enamorada,

yo siempre satisfecho,

los dos, un alma sola,

los dos, un solo pecho,

y en medio de nosotros

mi madre como un DÃos!

¡Figúrate qué hermosas

las horas de la vida!

¡Qué dulce y bello el viaje

por una tierra asÃ!

Y yo soñaba en eso,

mi santa prometida,

y al delirar en eso

con alma estremecida,

pensaba yo en ser bueno

por ti, no más por ti.

Bien sabe DÃos que ése era

mi más hermoso sueño,

mi afán y mi esperanza,

mi dicha y mi placer;

¡bien sabe DÃos que en nada

cifraba yo mi empeño,

sino en amarte mucho

en el hogar risueño

que me envolvió en sus besos

cuando me vio nacer!

Esa era mi esperanza…

mas ya que a sus fulgores

se opone el hondo abismo

que existe entre los dos,

¡adiós por la última vez,

amor de mis amores;

la luz de mis tinieblas,

la esencia de mis flores,

mi mira de poeta,

mi juventud, adiós! |

Quickly now, a snippet of cleanhanded searchlores: A method of finding free poetry that doesn’t step on any moral grass medians.

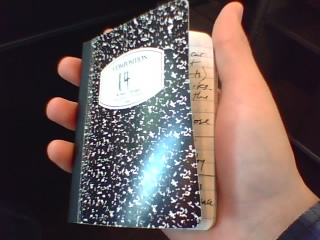

Quickly now, a snippet of cleanhanded searchlores: A method of finding free poetry that doesn’t step on any moral grass medians. I filled two small tear-out notebooks over that semester and continued after I left his class, writing in baby composition books with stitched binding. I admit, I stopped writing in them for about a year in college, but I carried a notebook in my back pocket even then. And I just started my fourteenth one.

I filled two small tear-out notebooks over that semester and continued after I left his class, writing in baby composition books with stitched binding. I admit, I stopped writing in them for about a year in college, but I carried a notebook in my back pocket even then. And I just started my fourteenth one.